Connecting the Dots for our Music Students and How We Can Help

“I don’t care who wrote it, I just want to hear good music!” is an all too common response I hear from the public when telling them about the work I do supporting women composers. I agree with this in theory, but this sentiment misses the crucial context of how women and gender-marginalized composers have been disempowered, excluded, and invalidated in this art form for centuries. Where do these misconceptions or attitudes come from and how early do they begin? The short answer is that musical knowledge and preferences start in the home and at school in our children's earliest memories.

As educators, we have a responsibility to our students and to the musical culture at large to provide the crucial historical and social context for students of all ages. It’s not enough to simply play music by women or other underrepresented composers and expect our students to have that “a-ha!” moment. We need to take them through why we are where we are, step by step, so they can learn early on to challenge notions of erasure and develop a curiosity and hunger for knowing more and diving deeper.

One of my favorite pieces of music by Lili Boulanger, “Les Sirènes” for women’s choir and orchestra or chamber ensemble.

As many of us educators and advocates know, the lack of knowledge of women composers in most people doesn’t often come from a lack of interest or even a true bias against the actual music written by women. Instead, it often stems from a complete lack of access on all possible fronts that has reinforced the idea that the music must “just not be that good if we haven’t heard about it.” But what happens when we present a reverse flow chart of sorts in which we break down all steps along the way that led to this common oversimplification? A common conversation we at BI frequently experience often looks like this:

Kathryn: Can anyone name some composers?

Audience: Mozart! Beethoven!

Kathryn: Fantastic! Now can you name a woman composer?

Audience: *silence settles in or an errant “Clara Schumann” is mentioned*

Kathryn: There are a lot of reasons why you might know few to no names. Why might we know the name Mozart more than, say, Clara Schumann, Ethel Smyth, or Florence Price, for example?

Audience: Because Mozart was cool/good/famous/a genius (the latter being the dirty word of classical music inequity)

Kathryn: Well, that’s all true, but what makes you think that women composers haven’t earned those same descriptors?

Audience: Well how good could they be if I’ve never heard of them?

Kathryn: Let’s explore how you know about the music you *do* know, and where your opinions first formed. Where did you first start listening to music?

Audience: Well, I guess I first heard it from my grade school music teacher?

Kathryn: Ok wonderful, and how did they choose that music?

Audience: I guess I don’t actually know?

Kathryn: Most likely, they were working with an established curriculum based on music that was taught to them when they were children and that was taught to their teachers when they were children, and on and on, going back decades and centuries. Now let’s think back even just to the beginning part of the 20th century. Whose voices were valued most in society and in culture? Who was allowed to have a voice?

Audience: Probably mostly men?

Kathryn: Specifically what kind of men?

Audience: White men, I suppose.

Kathryn: Yes, and music is no exception. Now let’s explore where music is heard. Where do you listen to music?

Audience: Live concerts, Spotify, CDs…

Kathryn: And what qualifications does music need to be recorded or programmed?

Audience: I’m not sure I actually know. Maybe just that the music has to be good or have withstood “the test of time?”

Kathryn: Certainly the music has to have a certain amount of inherent merit and be of interest, but what drives that interest are preconceived notions of what good music is and what good music is not. In addition to interest, there has to be funding at the onset of the recording process or through ticket sales for live events, as well as a promise of continued return on investment in the form of album sales and streams or concert attendance. That interest is, once again, formed from a very young age and passed down from parent to child and teacher to student for generations. In other words, if the people funding recordings and performances have inherent biases that were taught to them by an education system which also embodies these same biases, how would they stand a chance of being exposed to music that isn’t part of this inherited canon?

Audience: I guess I don’t know. Someone would have to play this new music for them?

Kathryn: Exactly! That’s where teachers, curators, conductors, historians, and performers come along.

If these conversations are happening with adults and lifelong professional musicians who still fall prey to reductionist thinking, can we really expect children to make different inferences without our guidance? The answer is no. Fret not, because in this challenge lies a fantastic opportunity to not only fill in the gaps of previous generations, but to learn about and share a wealth of incredible music by centuries of inspiring composers and enrich our sonic palate in ways that would make our predecessors rife with FOMO (to use the parlance of our youth).

Techniques for Educators

A great place for educators to start is to try incorporating even one 10-minute module into each week’s curriculum during which you introduce your students to one new woman or other underrepresented composer. Choose a compelling piece of music and a short clip, perhaps 45 seconds, and play it for the kids a couple times. Next is the important part: do not tell them who the composer is; remember, these biases start from a very young age and completely without their knowledge.

Make it a game! If they already know some composers, ask them who it might remind them of, what it makes them think of, how it makes them feel, what they think of it…get them to be as descriptive as possible so they develop a personal relationship with the music. Let them really sit with it for a moment. Then for the big reveal! Tell them the composer’s name and give them some fast facts about said composer such as their upbringing, education, who their contemporaries were, obstacles they faced, why they wrote music, etc. Continue to foster the relationship between your students and these composers that started when the students first listened to their piece and expressed opinions about the music.

An example slide from an elementary music educator in Denver, CO.

If you’re like the average music educator here in the United States, you might find yourself saying “But how will I make the time to find this information? I’m already swamped as it is!” That’s where Boulanger Initiative can help.

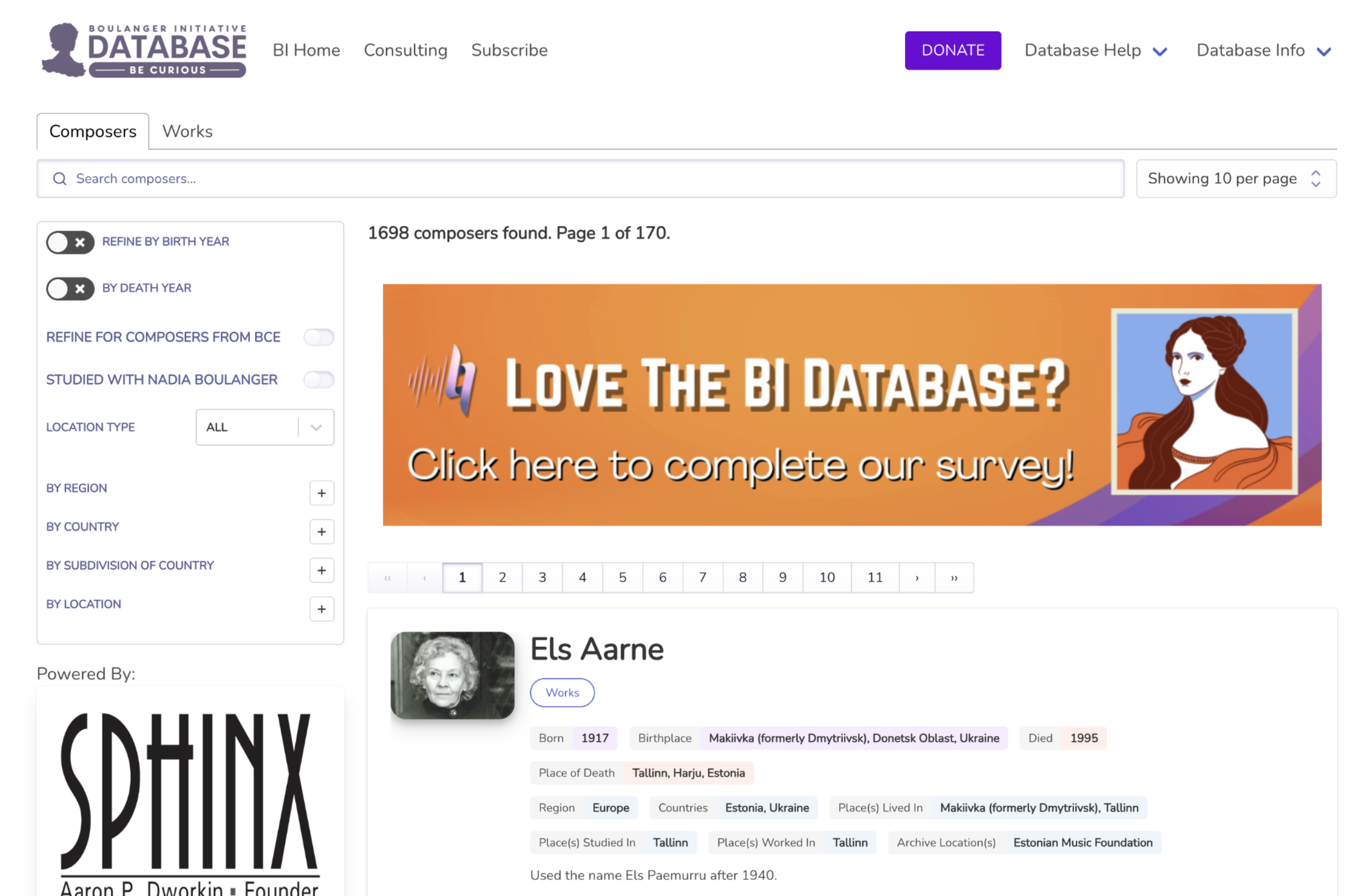

Our incredible Boulanger Initiative Database—the only one of its kind in the world—is free, open to the public, and dedicated solely to women and gender-marginalized composers and their works. Users can search by many criteria including instrumentation, date range of composition, composer name, birth region, and more. If scores, recordings, and other resources are available, they are linked right there in the database so any and all barriers to access are removed. At the time of this blog, it has 17,324 works from 1,698 composers from around the world, and it’s not hyperbolic to say we are constantly adding additional records with a dedicated team of Research Fellows and Associates (think Keebler elves with MENSA memberships) headed by our incredible Research Manager, Dr. Caiti Beth McKinney.

We’ve also created a published educational series called “Beyond the Box, Into the Barlines” (a nod to the egregious marginalization—quite actually relegated to the margins—of women composers in music history textbooks) all about women composers and their music, featuring composers from different eras, genres, or themes like the Baroque Era or women orchestral composers. If you’re seeking more curated assistance, we also offer affordable consultation services for individuals and education institutions looking for help finding repertoire/scores, building out lesson plans, choosing recordings, and so much more.

I frequently get asked, “What is the end goal?” and the eventual goal is to become obsolete. We dream of a world in which we don’t need to fight tooth and nail to ensure students are learning names like Florence Price or Julia Perry, the concert hall regularly and organically incorporates music by women outside the month of March, and the music-loving world might remark that a Benjamin Britten work reminds them of Ethel Smyth, and not the other way around.

-Kathryn Cruz

Director of Learning and Engagement, Boulanger Initiative