Serious or Silly? Exploring Liza Lehmann’s Five Little Love Songs

If you know one work by Liza Lehmann, it’s probably her art song “There are Fairies at the Bottom of Our Garden,” remembered in part due to its inclusion in popular anthologies. Maybe you heard it at a state festival or saw a clip of Julie Andrew’s 1972 television performance.

If your interaction with Lehmann’s music stopped at “Fairies,” you, like many before you, may have tucked her repertoire away in your memory as “lighthearted,” or perhaps “unserious,” fair descriptors for a song about a child’s imaginary fairy kingdom. During her lifetime, Lehmann was internationally known as the composer of In a Persian Garden, a song cycle for vocal quartet and piano which she called her “first serious composition” (Lehmann 1919, 70). This serious/light divide ungirds discussions of Lehmann’s music, with scholars focusing primarily on her earlier “serious” works while pushing her later “lighter” works aside. Yet, many of Lehmann’s more than 400 works do not fit neatly into this binary, including her brief song cycle for high voice and piano, Five Little Love Songs.

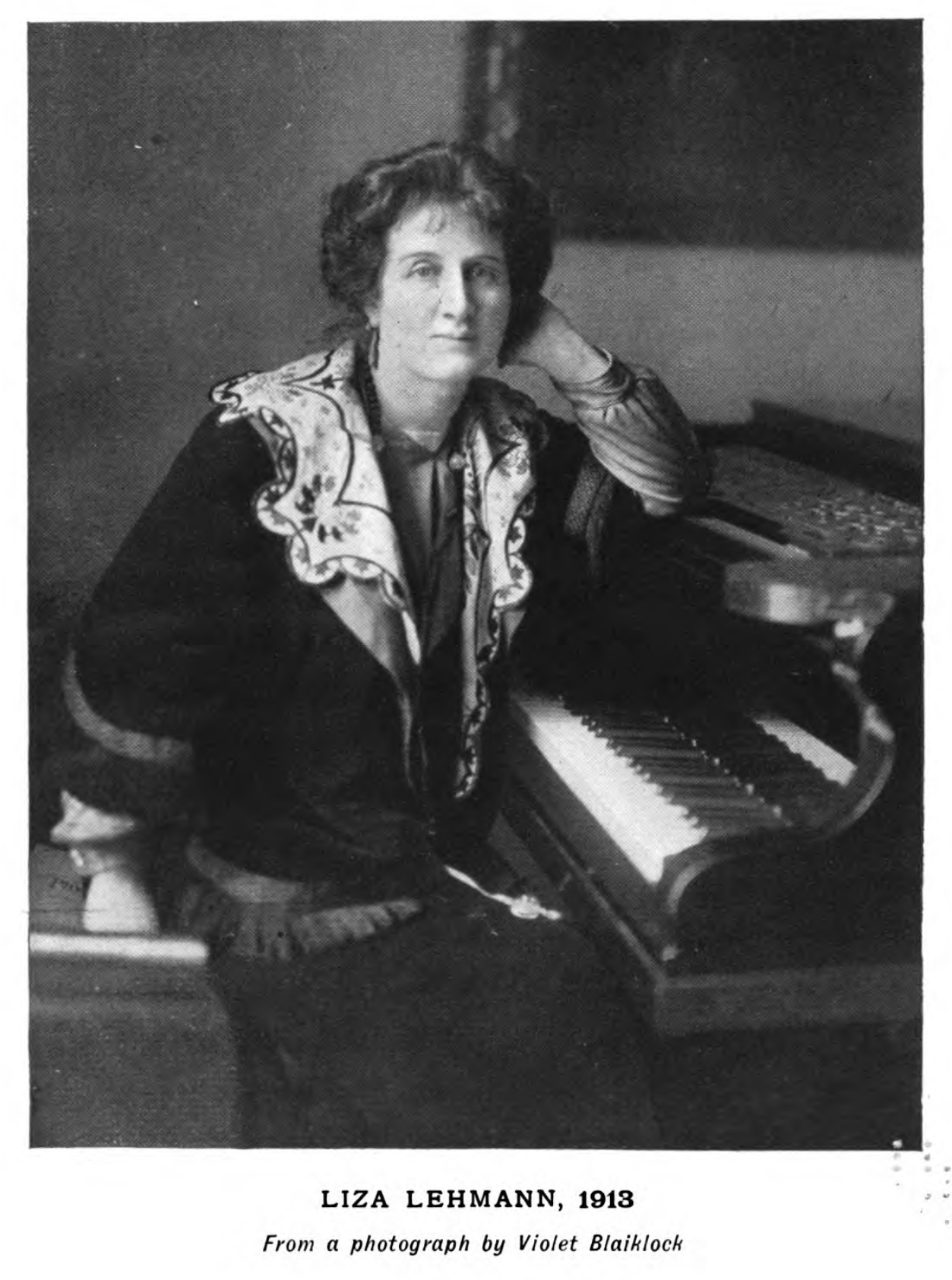

“Liza Lehmann 1913” Photograph by Violet Blaiklock. The Life of Liza Lehmann, 1919. Published by T.F. Unwin, courtesy of HathiTrust.

Watch the Unveiled Voices (Carl Alexander, soprano, Matthew Truss, contralto, Henry Pleas III, tenor, Vince Wallace, bass, and Charles Thomas Hayes, piano) give a dramatized performance of Lehmann’s break-out composition, In a Persian Garden, at a 2017 concert. Breaking with the Edwardian performance practice, the group substitutes countertenors for the two treble voice parts. The performance begins at 6:10.

“Sleeping Fay on a Lily” Sketch by Liza Lehmann. The Life of Liza Lehmann, 1919. Published by T.F. Unwin, courtesy of HathiTrust.

By the time Lehmann published the Five Little Love Songs in 1910, she was a veteran of the song-cycle genre, a genre which her contemporaries credited her for popularizing in England. The poetry comes from the American poet Cora Fabbri’s Lyrics, a collection published just after the young writer’s death. The first four songs adhere neatly to feminine compositional ideals of the Edwardian-era: dainty, charming, graceful, and tender. The topics also fit feminine stereotypes: birds, nature, love, and birds again. Seemingly, the cycle belongs to Lehmann’s “light” repertoire.

The final song, “Clasp mine closer, little dear white hand,” complicates this assessment. A stormy piano introduction grabs listeners, following the tinkling end of the fourth song. The piano shifts into a hymn-like texture to welcome the voice in. In this calm setting, the poetry reveals the song’s subject: death.

Clasp mine closer, little dear white Hand–

Clasp mine fastly, till it grows so cold

All your tender pressures will be vain

To awake an answ'ring touch again,

Till it lieth underneath the mould.

The singer shares their love for a companion, the dear white hand’s owner, expressing appreciation for their guidance. The contrasting middle section of the song, driven by a syncopated piano line, declares that “Paradise without you could not be.” As the voice climaxes on a high A, the piano explodes into a passage of rising chords, followed by the descending melody which opened the song. Short, stuttering phrases reflect the singer’s final breaths as the song draws to a close. While “Clasp mine closer” contrasts the earlier songs in harmonic language, affect, and form, it also casts a new understanding upon them, especially the second song. The opening motive of “Clasp mine closer” found its way into the closing phrases of the second song, “Along the Sunny Lane,” as well. What had been a charming–albeit melancholy–song about nature is now haunted by the spectre of the final song. Each verse’s insistence on the passage of time (“must pass,” “must hush,” “must pass away”) hints at the cycle’s conclusion. Even the joyous fourth song, a list of all the things the narrator would do “If I were a bird,” is inevitably answered in the final song: you are not a bird, you will never do those things. The youth of the first four songs never grows old. Taking the cycle as a whole, the songs lay between the cracks of “serious” and “light,” a reflection of their core themes: youth and death. Yes, these songs are about love, but love in a life cut short.

My point here is not to prove that the Five Little Love Songs are “serious” repertoire, and therefore worthy of study and performance. My point is to question the value of such designations in the first place, especially because at the turn of the 20th century the serious/light divide often mapped onto the composer’s gender. In continuing to classify music along this binary, we risk perpetuating gendered stereotypes and excluding music which does not adhere to the dichotomy. Lehmann’s Five Little Love Songs, and her repertoire at large, is light, serious, beautiful, and meaningful all at once.

Soprano Lindsay Campbell and pianist Neill Campbell perform Lehmann’s Five Little Love Songs at the 2025 concert “In Her Own Voice.”

To learn more, visit this Further Reading link!

Bibliography

Five Little Love Songs. 1910. With Liza Lehmann and Cora Fabbri. Chappell & Co.