Mel Bonis, Compositeur de Musique

French composer Mélanie Bonis (1858-1937) wrote nearly 300 musical works in numerous genres. Nearly lost to history, they lay dormant in boxes until their rediscovery in the 1990s. During her studies, she adopted the androgynous pseudonym, “Mel Bonis,” hoping that if her gender were obscured, her work would be taken seriously–work that has recently soared in popularity, though little is yet known about the composer behind the pseudonym.

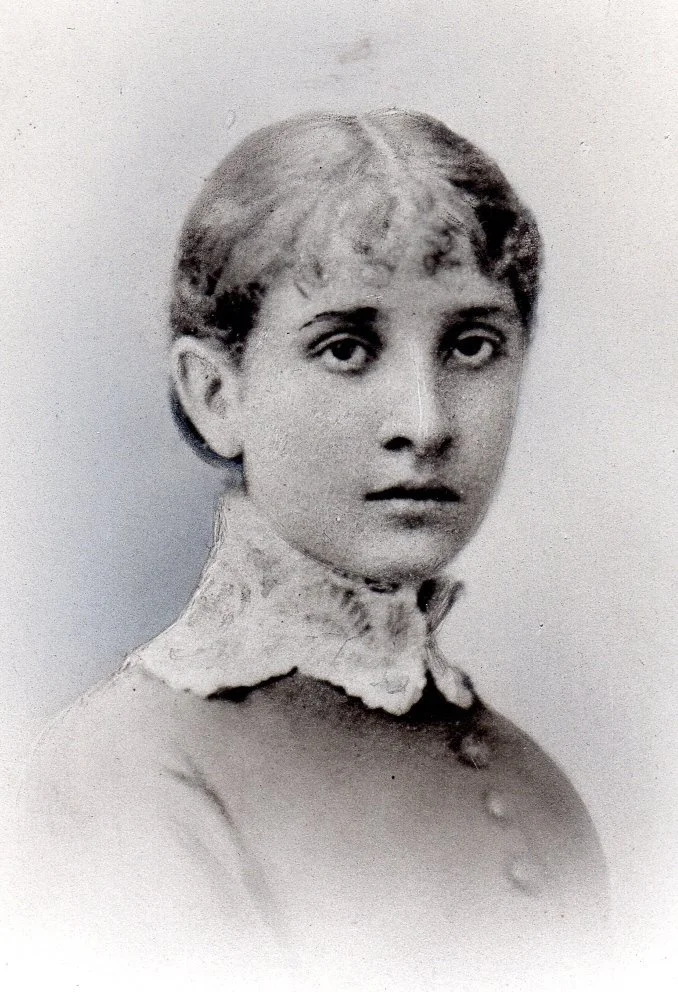

Mélanie Bonis, ca. 1880

Image: © Bru Zane Mediabase / fonds Bonis

The available biographical sources were written by her descendants, and the accolades and omissions of the earliest, published in 1947, betray their efforts to shape her legacy. Étienne Jardin, contributing editor of the volume, Mel Bonis (1858-1937): Parcours d'une compositrice de la Belle Epoque, cautions readers against perpetuating her descendants’ account as truth. Jardin points to several critical problems with this work, not the least of which is the fact that their account of her early years was written nearly a century after the events by people who were not there to witness them (Jardin, p. 4). Their information may have come directly from Bonis, but her complicated relationship with her parents must also be taken into account when assessing the veracity of this narrative (Jardin, p.4). Bonis’ children write of a child prodigy whose parents tried to keep her away from music. When finally allowed piano lessons, she sprinted toward her 1876 entrance to the Paris Conservatoire, then soared past her studies into a period of “great artistic fertility” (Mel Bonis, p. 3). Her children make no secret of her “fragile” health, insomnia, and depression, but the secrets they do keep perhaps explain these sufferings (Géliot, 2010, p. 3).

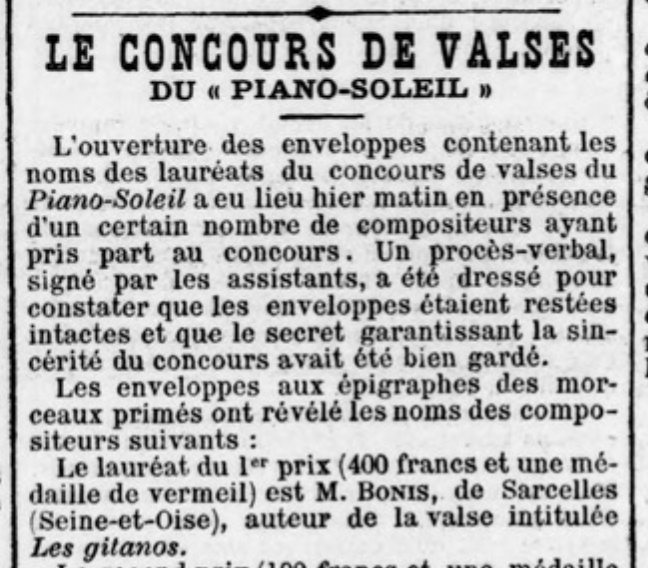

Le Soleil Oct 13, 1891

Image source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Bonis’ great-granddaughter, Christine Géliot, has filled in important details, though she herself stated in the introduction to her book that her writing does not always “adhere to the strict rules for writing a biography such as are observed by musicologists” (Géliot 2010, 3). At the conservatory, Bonis fell in love with fellow student Amedée Hettich. Her parents rejected the match and pulled her out of school in 1881, her studies incomplete and her aspirations frustrated. In 1883, they arranged her marriage to Albert Domange, an older, wealthy widower who was indifferent to music (Géliot, n.d.-a). We don’t have a record of her own thoughts about this arrangement, but a family anecdote relates that she once quipped, “If I’m forbidden to have love, I’ll take the money!” (Géliot, 2010, p. 15). Bonis disappeared into domesticity for about a decade, raising the Domange children in Sarcelles, safely removed from the dangers of the city (Jardin, p.7). She composed very little, though extant correspondence with Ernest Guiraud, her composition professor at the Conservatoire, shows both his belief in her talent and her desire to continue composing (Géliot, n.d.-a). In 1891, she won first prize in a composition competition sponsored by the music journal Piano-Soleil with her waltz titled Les Gitanos. She was initially congratulated in print as Monsieur Bonis because of her pen name!

Mélanie Bonis, n.d.

Image: © Bru Zane Mediabase / fonds Bonis

In 1898, the Domange family moved back to Paris, which is likely what brought her again into contact with Amadée Hettich (Jardin, p. 9). He was by now a well-respected vocal pedagogue and was working as editor of the music journal l'Art musical (Géliot, n.d.-a). Hettich would be pivotal in Bonis’ return to music. He introduced her to important figures in the Parisian music world, including Alphonse Leduc, whose publishing house owned l’Art musical, and who would soon become Bonis’ publisher (Géliot, 2010, 23). He also encouraged her to compose—support that she lacked elsewhere. Hettich and Bonis once again collaborated as they had done at the conservatory, his words embraced by her music. No one really knows when it began, but the former sweethearts began a love affair. In 1899, ostensibly in need of a “health cure,” Bonis traveled abroad to hide the growing evidence of their affair. She returned to Paris covertly in time to give birth to their daughter Madeleine, who was left in the care of foster parents—a trusted former housemaid and her husband (Géliot, 2010, pp. 60-61).

Bonis returned home with empty arms and a terrible secret. She was never quite the same. No one but Hettich knew the true reason for her journey, and their secret would remain hidden for many years to come. Though their affair ended with the birth of their daughter, the lovers remained in contact to see to Madeleine’s wellbeing. Bonis would, for now, act as a sort of godmother to her. To ease her agonized conscience, she turned to prayer and to music. Rather than the piano pieces and songs she published in the 1890s, she now focused on “serious” chamber music and religious works (Géliot, n.d.-a). She was active in the Société des compositeurs de musique, mingling with the likes of Gabriel Fauré and Maurice Ravel (Géliot, n.d.-b). Her works were heard throughout Paris, and though reticent, she sometimes performed them herself. Critics reviewed her music in positive terms, though much of it reads as sexist today–Camille Saint-Saëns raved over her piano quintet, astonished that a woman could write music of such quality (Géliot, n.d.-a).

Mélanie Bonis, ca. 1900

Image: © Bru Zane Mediabase / fonds Bonis

The late 1910s inflicted fresh agonies on Bonis’ keenly sensitive soul. She was widowed in 1918. During the first World War, her sons, step sons, and son-in-law served in the military (Mel Bonis, p. 3). Édouard, her youngest, was taken prisoner (Géliot, n.d.-a). Her children report that she poured her energies into charitable works in support of the war effort, even taking four war orphans into her personal charge (Mel Bonis, p. 3). What her children neglect to mention is that one of the “war” orphans was Madeleine, whose foster mother died near the beginning of the conflict. It was a great comfort to his mother when Édouard returned home after the war’s end, but comfort was replaced with what must have been utter torment as she witnessed the unfolding romance between her son and the lovely new resident of Chez Domange, Madeleine. Bonis was left with no choice. She revealed to Madeleine alone her most painful, most shameful secret, then forced her to swear secrecy “before God” (Géliot, 2010, p. 133). A secret of this nature, at this time in history, would have “shattered the honour of the whole family,” according to Géliot. (MB). It was Madeleine instead who was shattered. Géliot writes that she “never recovered” from being excluded from her own family, especially while living with them, and much like her mother, never recovered from the loss of her first love (Géliot, n.d.-a).

The Domange Family playing Bonis’ Symphonie burlesque, ca. 1920. Bonis is at the piano.

Image: © Bru Zane Mediabase / fonds Bonis

Mel Bonis today is a figure revealed in fragments of incongruent personalities–Mélanie Bonis, music student; Mel Bonis, composer; and Madame Domange, wife and mother. These identities mask the complex humanity of a woman whose life, despite her convictions, transgressed her prescribed boundaries (Géliot, n.d.-b). This tension between who she was and who she believed she should be is perhaps the most compelling (and relatable) element of her story–made evident in the tension between her “moral rigidity” and the “extraordinarily bold sensuality” of her music (Géliot, n.d.-b). Bonis herself described the work of art as something like a mirror, inevitably reflecting the “essential being” of its creator (Bonis, 1974, p. 40). Perhaps the best way for any of us to encounter the real Mélanie Bonis is through her music. Perhaps that’s what she hoped for all along.

References:

Bonis, Mel. Souvenirs et réflexions. Edited by Jeanne Brochot. Les éditions du Nant d'enfer, 1974. https://www.bruzanemediabase.com/en/node/14655.

Géliot, Christine. (n.d.-a). “Mel Bonis (1858-1937),” Musica et Memoria. Accessed October 18, 2025. http://www.musimem.com/bonis.htm.

Géliot, Christine. (n.d.-b). “Biography: Mel Bonis, 1858-1937.” Translated by Florence Launay and Michael Cook. Accessed October 18, 2025. https://www.mel-bonis.com/EN/Biographie/.

Géliot, Christine. “Mel Bonis, the Woman and the Composer (1858-1937). Translated by Dilys Barré. l’Harmattan, 2010.

Jardin, Étienne. “Introduction.” In Mel Bonis (1858-1937): Parcours d'une compositrice de la Belle Epoque, edited by Étienne Jardin. Actes Sud, 2020.

Mel Bonis (Madame Albert Domange), Compositeur de Musique: Biographie–Œuvres, Par ses Enfants et Petits-Enfants à l’occasion du dixième anniversaire de sa mort. March 1947.