“By a Linden Tree”: Discovering the Lieder of Composer Ethel Smyth (Part 2)

Lieder & Balladen, Op. 3 (1886)

Portrait of Smyth (1910) | John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) | Wikipedia

By the winter of 1878, Smyth had befriended the Herzogenbergs. The couple “adopted” the young composer into their lives, reserving a room for her in their home. Smyth became particularly close to Elisabeth, who was eleven years her senior, affectionately calling her Lisl.

“From now onwards I became, and remained for seven years, a semi-detached member of the Herzogenberg family… not a day passed but that one or other of my meals was taken with them… the little spare room, stocked for my needs, was always ready when required…” (Smyth 1919, 272-273).

During her Leipzig years with the Herzogenbergs, Smyth composed Lieder & Balladen, Op. 3, some time between 1877 and its publication in 1886. The opus contains five songs: “Vom Berge” (From the Mountain), “Der verirrte Jäger” (The Lost Hunter), “Bei einer Linde” (By a Linden Tree), “Es wandelt, was wir schauen” (What we look at, it changes), and “Schön Rohtraut” (Pretty Rohtraut).

Smyth drew from two literary sources – the first four songs employ poetry by Joseph von Eichendorff (1788-1857), while its final song, “Schön Rohtraut,” is a ballad set to poetry by Eduard Mörike (1804-1875). At elite salon gatherings, Smyth would perform some of these early song compositions for German composer and pianists Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) and Clara Schumann (1819-1896).

“Bei einer Linde” (By a Linden Tree)

The third song of Lieder & Balladen, Op. 3, “Bei einer Linde” (By a Linden Tree), invokes the memory of a lost love affair through the enduring growth of a linden tree. Smyth’s seven-year romance with Elisabeth von Herzogenberg was intact as she composed “Bei einer Linde.” By its publication in 1886, their romance had irrevocably severed.

Musicologist Jürgen Thym observes that song as memory was “a topos visited many times in the nineteenth Century, especially by composers of Lieder” (Thym 2012, 263). While “Bei einer Linde” does not reference Elisabeth directly, it serves as a potent metaphor to retroactively frame “the very tenderest relation” that “governed [Smyth’s] life both humanly and musically for so many years” (Smyth, 179, 181). “Bei einer Linde” expresses nostalgia for a past that no longer exists, not unlike the act of Smyth memorializing her own relationship with Elisabeth in her memoirs.

Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff (1788-1857)

Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff (1832) | Etching by Franz Kugler (1808-1858) | Wikipedia

The author of “Bei einer Linde,” Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff, was considered one of the great lyric poets of the German Romantic era. Born into a noble family in Upper Silesia (now Poland), Eichendorff’s younger years were marked by the violence of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815).

As he studied law in Halle and Heidelberg, Eichendorff was introduced to leading writers of the Frühromantik (Early Romantic), including Achim von Arnim (1781-1831) and Clemens Bretano (1778-1842). By 1822, his family had lost their ancestral estate of Schloß Lubowitz, and he worked as a civil servant in the Prussian government until his retirement in 1844.

Despite his career in public administration, Eichendorff wrote voluminously - as a poet, novelist, playwright, editor, translator, literary critic, and anthologist. Eichendorff’s poetry, encapsulated in his 1837 collection Gedichte (Poems), often imitated the subject matter and versification of folk songs. He wrote in a straightforward style with simple language, engaging with Romantic themes of nature, wandering, love, the passage of time, nostalgia for the past, and the supernatural.

Eichendorff was one of the most popular Lieder poets, set by composers such as Mendelssohn, Brahms, Robert Schumann, Hugo Wolf (1860-1903), Richard Strauss (1864-1949), and of course, Ethel Smyth. It speaks to Smyth’s savviness and assimilation into German-speaking culture that she would choose to set Eichendorff as the primary poet of her first set of Lieder (songs).

“Bei einer Linde”: The Poem

Illustration of a large linden tree at a cemetery in Annaberg, Austria (c. 1886) | Alamy

In “Bei einer Linde,” we encounter a scene in nature. Our protagonist visits a linden tree, where they and their beloved once carved their initials in springtime. The years have passed; their relationship has ended. The tree has now grown from a sapling into an adult with hardened bark. The couple’s initials, akin to their love, have been erased from its overgrown branches. In the shade of the tree, our protagonist admits that they’ve never healed from this past love and believe that they never will.

Bei einer Linde

Seh ich dich wieder, du geliebter Baum, In dessen junge Triebe Ich einst in jenes Frühlings schönstem Traum Den Namen schnitt von meiner ersten Liebe? Wie anders ist seitdem der Äste Bug, Verwachsen und verschwunden Im härt’ren Stamm der vielgeliebte Zug, Wie ihre Liebe und die schönen Stunden! Auch ich seitdem wuchs stille fort, wie du, Und nichts an mir wollt weilen, Doch meine Wund wuchs - und wuchs nicht zu, Und wird wohl niemals mehr hienieden heilen. Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff (1788 - 1857) Aus *Gedichte* (1837) in *4. Frühling und Liebe*

By a Linden Tree

Will I see you again, you beloved tree, Who, as a young sapling, I once, in spring’s most beautiful dream, Carved the name of my first love? How different are the sloping branches since then, Overgrown and disappeared The much beloved lines in the hardened trunk, Like her love and our lovely hours! Since then, I too grew in silence, like you, And never wanted to linger, But my wound grew – and did not close, And will nevermore heal this side the grave. Translation by Dr. Noelle McMurtry

“Bei einer Linde”: The Music

Listen to baritone Maarten Konisberger and pianist Kelvin Grout's performance of "Bei einer Linde" from the 2012 album "Ethel Smyth: Kammermusik and Lieder, vol. iv."

In Smyth’s conception of “Bei einer Linde,” her musical setting remains compact, yet never lacking in originality. She refrains from overriding the poem’s existing structure and language, while still offering her own harmonic and motivic ideas on the text.

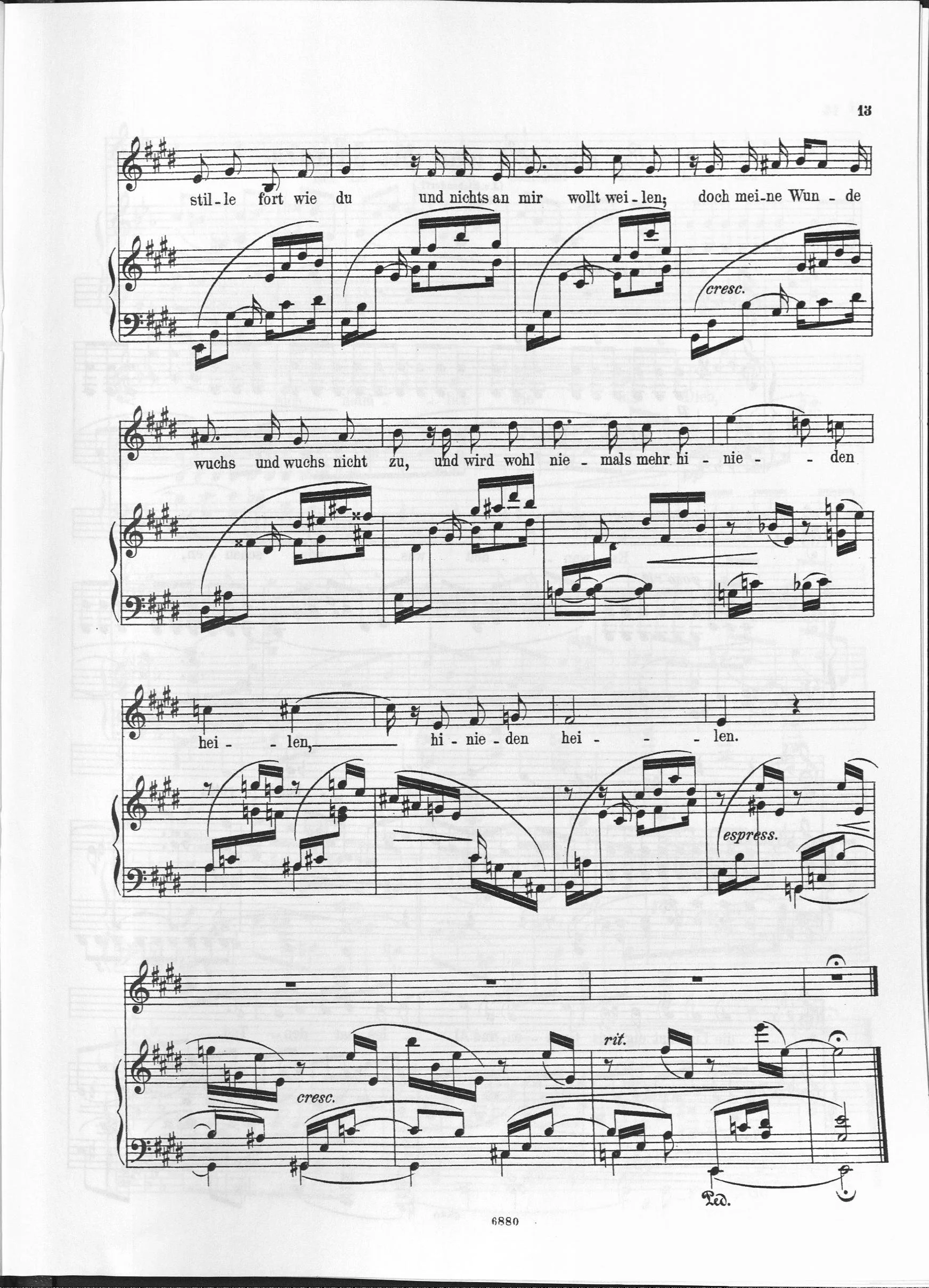

Check out the score for "Bei einer Linde" from Lieder & Balladen, Op. 3 (1886), published by C.F. Peters in Leipzig.

As a poem, “Bei einer Linde” is constructed of three stanzas of four lines, each following a predictable ABAB, CDCD, etc. rhyme scheme. For her part, Smyth honors the three-stanza structure of the poem by composing her musical version in three sections - A, B, and A1 (or a repetition of A with modifications).

Smyth further delineates her stanza structure through key modulation - E Major to G Major, and a final return to the home key of E Major. For the listener, this modulation to a minor third above is noticeable. It dramatically illustrates the protagonist’s shift in perspective from their past relationship to their present reflections on the tree throughout the second verse of the poem.

Smyth also retains the poem’s original versification, adding little repetition save ,,hienieden heilen” (to heal this side the grave) twice at the song’s conclusion. This sole moment of textual repetition creates a sense of finality, backing the protagonist’s admission that they may never truly heal from their lost love.

In another instance of text painting, Smyth employs an arpeggiated sixteenth-note figure in the piano line. From its onset in the song’s first section, this arpeggiation becomes an instantly-recognizable motif. It evokes a nostalgic pathos that aligns with the protagonist’s remembrance of their former relationship.

As this musical figure reappears in the third and final section of “Bei einer Linde,” it becomes even more extended in its range, heightening the unresolved tension inherent in our protagonist’s reflections.

The Linden Tree

19th-century illustration of a couple under a linden tree, after the soldier's return from the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) | Alamy

It’s important to also discuss the powerful symbolism of the linden tree as a “‘sacred’ tree of… lovers” in German Romantic poetry (Ţenche-Constantinescu et al. 2015, 239). Belonging to the genus Tilia, the linden (or lime) tree is found in Asia, Europe, and eastern North America. It comprises over 30 different species of trees, which can grow over 100 feet tall with heart-shaped leaves.

For thousands of years within various cultural practices, linden trees have represented love, truth, peace, justice, prosperity, fidelity, and fertility. During the Middle Ages in western Europe, tradition dictated that lovers should swear their fidelity under a linden tree, whose truth-telling powers made it impossible for the couple to lie (Ţenche-Constantinescu et al., 239).

By the mid-19th Century in Germany, linden trees were often referenced in poetry and subsequently surfaced in song settings. The Romantic-era preoccupation with the natural world as a reflection of an individual’s inner life transformed the linden tree into a ripe symbol of love lost or gained.

For example, the fourth song of Franz Schubert’s famous 1828 song cycle Winterreise (Winter’s Journey) is aptly titled “Der Lindenbaum” (The Linden Tree). Having been rejected by their lover, the cycle’s grief-stricken protagonist wanders through a desolate, winter landscape. Akin to Smyth’s protagonist in “Bei einer Linde,” they come upon a linden tree, where they had once carved their beloved’s name.

In the freezing night, the tree invites them to find Ruhe (rest) under its branches. Instead of serving as a nostalgic reminder of what-could’ve-been, the tree now encourages the poem’s protagonist to seek solace in death.

Watch a recording of Schubert's “Der Lindenbaum” with American mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato and Canadian conductor and pianist Yannick Nézet-Séguin from a 2019 concert in Carnegie Hall.

Lisl & Ethel

How exactly then is “Bei einer Linde” a means of better understanding Smyth’s relationship with Elisabeth von Herzogenberg? Not only was the song’s composition heavily influenced by Smyth’s time in Leipzig with the Herzogenbergs, but the relationship that it describes - one of first love, hope, the spectre of a shared life, and ultimate fragmentation - mirrors the eventual dynamic between the two women. As Smyth herself wrote, “If ever I worshipped a being on earth, it was Lisl” (Smyth, 185).

19th-century illustration of a sick woman on a bed in a cottage living room | Francis Wilfred Lawson (1842-1935) | Alamy

In the spring of 1878, as the young composer suffered from (what she described as) a “severe illness… really a nervous breakdown,” Elisabeth personally nursed her friend for over two weeks (Smyth, 180). She remained by Smyth’s bedside day in and out, “..washing me herself, performing all the sick-room offices for me, cooking on her own little cooker… reading to me, alternately petting and keeping me in order” (Smyth, 181).

Their relationship was complex from the outset, and the two women often compared their dynamic to that of a parent and child. Elisabeth, who suffered from heart disease, could not have children, a reality that caused her lifelong sadness. Due to Elisabeth being eleven years older, she initially regarded Smyth as both the child she could never have and a younger composer to take under her wing.

However, Smyth and Elisabeth’s relationship soon veered into the romantic. After Smyth’s health improved enough for Elisabeth to embark on a trip to Austria, she wrote letters to the recuperating composer every day, sending chocolates, flowers, and books to her door. By the summer of 1878, as Smyth returned to England for a family visit, their affection for one another was fixed.

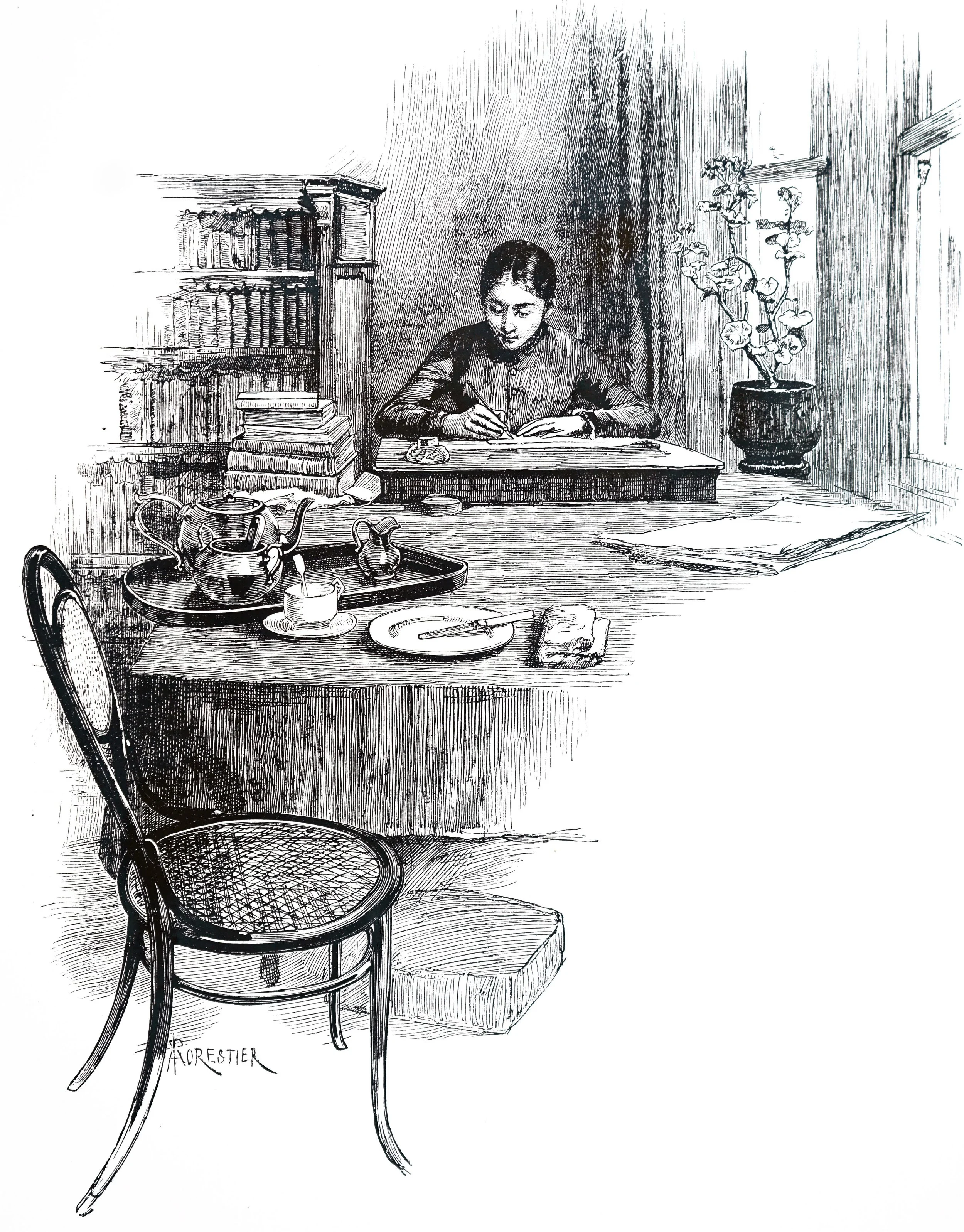

19th-century illustration of a young woman writing a letter at her desk | Alamy

In an excerpted letter, Elisabeth wrote to Smyth about managing the pain of their brief separation,

“... that cannot change the fact that we love each other… My child, I wonder sometimes at the different ways Fate spins the thread which binds people together – how it often takes years to enter into possession, and how in our case something has grown between us that tells me we belong together, inseparably! (Smyth, 223).”

For Smyth, the feeling was mutual. In an 1878 letter to her mother, she wrote, “What is it in Lisl that none can resist, old, young, rich or poor?... One can’t envy Lisl anything, she deserves all the love a mortal can give her…” (Smyth, 288).

As their relationship developed, Elisabeth’s husband Heinrich was aware of their bond. It’s unclear, though, how he qualified his wife’s relationship with the young English composer. By 1880, Elisabeth even mentioned to Smyth that Heinrich did sometimes find their “ménage á trois” tedious, but he accepted it nonetheless (Smyth, 288).

The ,,Lebensteufel” of Ethel Smyth

In the autumn of 1881, after a family visit to England, Smyth returned once more to Leipzig. Over the past three years, her relationship with Elisabeth had matured, although Smyth now sensed a distance forming between the two women.

It didn’t help matters that Smyth, as an energetic 23-year-old, was only too eager to explore all that life had to offer. She had a self-attributed “knack of constantly forming new ties,” a trait which – as author Rose Collins dryly notes in Portraits to the Wall: Historic Lesbian Lives Unveiled – made her “something of an emotional magpie” (Collins 2020).

For her part, Elisabeth wished to maintain their well-established intimacy in Leipzig (Smyth, 302). She believed that Smyth was too motivated by Lebensteufel (life’s devil), a restless desire to seek out new experiences, no matter the cost (Smyth, 304).

Although Christmas was always spent with the Herzogenbergs in Leipzig, Smyth announced her plans to travel to Italy and Switzerland the following winter. In Italy, Smyth would make “contact with other forms of beauty than music” (Smyth, 303). Over the past four years, she had dutifully studied composition with Heinrich, and now clamored for fresh inspiration and the opportunity to compose independently of her teacher.

The Brewsters of Florence

A year later, in the fall of 1881, Smyth set out for Italy. In Florence, she would befriend an eccentric couple – the Brewsters. They were “hermit-like,” avoided most of society, and lived on the historic Via de’ Bardi with their two children (Smyth, 312).

Julia Brewster (1842-1896) (née von Stockhausen) was Elisabeth’s older and much beloved sister. Her husband, Henry Bennet Brewster (1850-1908), whom we met earlier in this post, was a British-American philosopher and writer. He was also the man “destined to become [Smyth’s] greatest friend” and the ultimate source of her disastrous rupture with Elisabeth (Smyth, 313).

A cityscape of Florence, Italy from the terrace of San Miniato (c. late 19th Century) | Alamy

The Brewsters, as Elisabeth described to Smyth in a letter, “lived in a world of their own” – they only spoke formal French to one another at home, Julia was eleven years older than her husband, and the pair maintained “extraordinary views on marriage” (Smyth, 312).

They were wed in a church ceremony so as not to distress Julia’s parents, but in reality, the Brewsters did not practice marriage as a “binding engagement” (Smyth, 312). Smyth described their philosophy as follows:

“If either of the couple should weary of married life, or care for someone else, it was understood that the bond was dissoluble, and there was a firm belief on both sides that no such event could possibly destroy, or even essentially interrupt, their "friendship" as they called it, founded as it was on more stable elements than mere marriage ties. ‘Do not be afraid,' they said, ‘of anything life may bring; face it, assimilate it, and the gods will see you through’” (Smyth, 312).

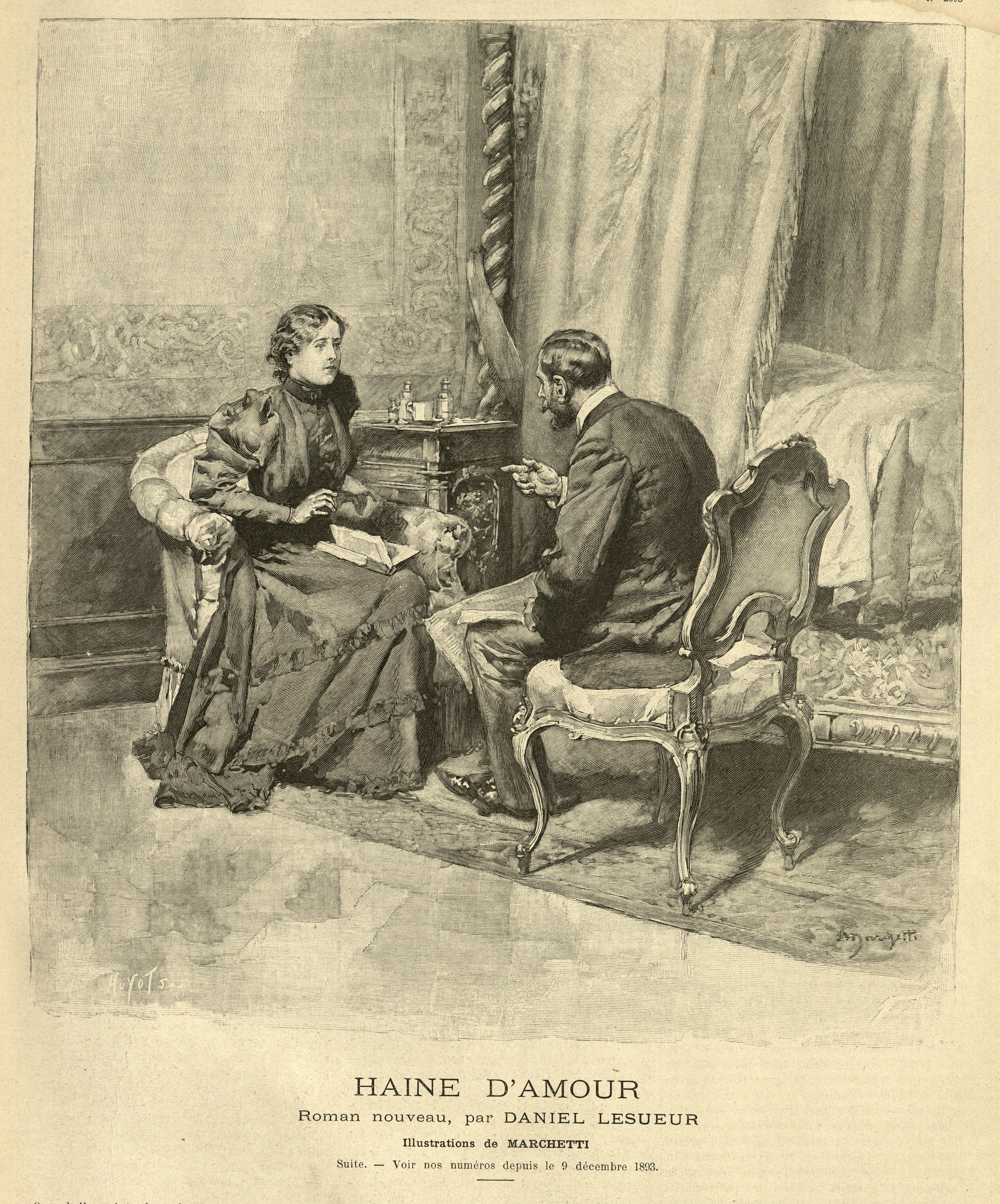

Victorian illustration of man and woman in discussion over a book (c. 1890s) | Alamy

The Brewsters discussed this pact openly – to release each other from their union if they fell in love with another – although Smyth noted that it was “only as a general thesis,” and had yet to be tested (Smyth, 314). Initially, Smyth found Henry to be shy, but they soon found common ground with discussions on literature, philosophy, politics, and art. She wrote, “[Henry] seemed to have read all books, to have thought all thoughts; and last but not least was extremely good looking… It was the face of a dreamer and yet of an acute observer, and his manner was the gentlest, kindest, most courteous manner imaginable…” (Smyth, 313-314).

Over the next two winters, Smyth spent time with the Brewsters in Florence. While Smyth was originally drawn to Julia, she unexpectedly found herself enjoying time with Henry more and more (Smyth, 169). Just as Smyth had formed a sort of triangle with the Herzogenbergs in Leipzig, she now found herself pulled into yet another triangle - this time, with the Brewsters in Florence.

The Brewsters discussed this pact openly – to release each other from their union if they fell in love with another – although Smyth noted that it was “only as a general thesis,” and had yet to be tested (Smyth, 314). Initially, Smyth found Henry to be shy, but they soon found common ground with discussions on literature, philosophy, politics, and art. She wrote, “[Henry] seemed to have read all books, to have thought all thoughts; and last but not least was extremely good looking… It was the face of a dreamer and yet of an acute observer, and his manner was the gentlest, kindest, most courteous manner imaginable…” (Smyth, 313-314).

Over the next two winters, Smyth spent time with the Brewsters in Florence. While Smyth was originally drawn to Julia, she unexpectedly found herself enjoying time with Henry more and more (Smyth, 169). Just as Smyth had formed a sort of triangle with the Herzogenbergs in Leipzig, she now found herself pulled into yet another triangle - this time, with the Brewsters in Florence.

A Love Triangle Gone Awry

As you can imagine from the tale of “Bei einer Linde,” the Brewster-Smyth love triangle proved to be combustible. After knowing Smyth for only a few weeks, Henry confessed to his wife that he had fallen in love with her. In turn, Julia suggested that he leave immediately; the pretense was a lion-hunting expedition in Algeria, but it was actually a means of distancing himself from Smyth. Fortunately, Smyth notes that he “achiev[ed] nothing more than once hearing a lion roar in the distance” (Smyth, 315).

For her part, Smyth was blissfully unaware of Henry’s feelings. In 1884, after spending two winters with the couple in Florence, Smyth finally admitted that she too was in love with him. From that moment on until his death in 1908, Smyth and Henry would maintain their complicated bond.

However, the fallout of their attraction to one another was chaotic; it bulldozed some of Smyth’s most cherished relationships, particularly with Elisabeth. As author Rose Collins suggests, “For the next ten years or so, this odd couple upset everybody with their on-off intense romantic friendship” (Collins 2020).

Smyth felt it was impossible to continue on as they were, and she decided to cut off all contact from Henry. Upon returning to Leipzig in 1884, Smyth revealed everything to Elisabeth, and they initially “saw eye to eye in all points, and parted, as may be imagined, more closely if more tragically knit than ever” (Smyth, 366).

Illustration of two women intimately conversing (1890) | Alamy

While Smyth claimed that she didn’t meet Henry again for another five years out of deference to Julia, the trio continued to write letters in an attempt to reconcile their “situation.” Henry wished to abide by the Brewsters’ much-discussed pact to dissolve their union. Julia was devastated by what she viewed as Henry and Smyth’s betrayal.

19th-century illustration of women conversing | iStock

Smyth was torn between her love for both Elisabeth and Henry, the fear that society would label her an “adulterer,” and total incredulity at the fact that Julia had presented herself as far less invested in her marriage than she actually was. Although Smyth takes great pains in her memoirs to describe the actions of all involved as honest and level-headed, the reality was that Julia had no intention of neatly removing herself from her own marriage.

On Smyth’s part, it seems intensely naive to not fully comprehend how this revelation would wound Elisabeth. Not only was Smyth in love with another person, but he was also her sister’s husband. It placed Elisabeth in an impossible position - to choose between her loyalty to Smyth or to her family.

By the winter of 1884, Heinrich von Herezogenberg had been offered a new teaching position in Berlin, and the Herzogenbergs prepared to move from their beloved Leipzig. After having cut all (in-person) contact with Henry, Ethel hoped to eventually join them in Berlin.

However, news of the Brewster-Smyth triangle spread amongst their family and friends. Elisabeth’s mother and brother, who had never approved of Smyth, privately campaigned for Elisabeth to cease all contact with the English composer. From their biased perspective, Smyth was entirely to blame. How could Elisabeth continue any relationship with the person responsible for the demise of her sister’s marriage? This familial pressure, as well as experiencing Julia’s sadness firsthand, overwhelmed Elisabeth.

A year later, in May 1885, Smyth accompanied the Herzogenbergs to the train station in Leipzig. She said her goodbyes on the platform with the caveat that she would soon join them in Berlin after a trip home to England.

19th-century illustration of woman waving farewell on the train platform | Alamy

As Smyth wrote Impressions That Remained over forty years later, this scene at the train station remained forever seared into her mind - Lisl waving, her face framed in the train window. “I remember few dates, but that date, May 7, will be remembered to my dying day. As the train moved off and slowly rounded the curve, I saw Lisl still waving at the window… never to see her again in this world, except in dreams” (Smyth, 352).

The Final Rupture

By the summer of 1885, now in separate countries, Smyth worried incessantly about the future of her relationship with Elisabeth. Their lives had revolved around one another for the past seven years, and Smyth simply couldn’t envision a future without her.

By June, after visiting with her brother, Elisabeth’s tone in her letters changed. As Smyth notes, “The work of disintegration had begun” (Smyth, 369). Then, without a word, Elisabeth stopped writing. They had once written to each other every day.

Two months later, a letter finally arrived. In no uncertain terms, Elisabeth informed Smyth that, despite the pain it caused them both, their relationship was over. She accused Smyth of being “a wild horsewoman blinded by self-love, galloping rough-shod over all [she] met…” (Smyth, 371). Elisabeth blamed herself for not cutting off association with Smyth sooner, and while she admitted that she didn’t think Smyth capable of actively deceiving anyone, “... of what avail are innocence and excellent intentions if none the less devastation marks your path?” (Smyth, 371). As she read these harsh words, Smyth admitted that she finally saw herself through Elisabeth’s eyes, “not as a co-adjutor in a noble reading of Destiny, but simply as [a] thief of someone else’s goods…” (Smyth, 371).

Smyth begged Elisabeth by letter to reconsider, but after exchanging a few more missives, Elisabeth fell silent. Except for a single letter two years later, they would never speak to or see each other again. Smyth never gave up hope that they would one day reconcile, and she followed Elisabeth’s activities from afar through mutual friends.

Seven years later, in 1892, Smyth was devastated to learn from Henry that Elisabeth had died unexpectedly in San Remo, Italy - from complications due to her heart condition.

Epilogue

In 1895, three years after Elisabeth’s death, the Brewsters finally divorced. Julia would die a year later - from the same heart condition as her younger sister. Smyth and Henry’s romance, friendship, and creative partnership continued until his own death in 1908; they would write around 1,000 letters to one another (Harris, 72). Although Henry asked Smyth to marry him several times, she refused.

In 1886, as Elisabeth abruptly ended their relationship, Smyth was thirty-four years old. This rupture signaled the beginning of the end of Smyth’s time in Leipzig. She wrote of her forced sense of self-resignation, “The strands of what was to become the fundamental friendship of my life were severed, not to be re-joined for many years. I burned my boats and went into the desert” (Smyth, 373).

Victorian illustration of a woman crying on her bed from the British magazine The Quiver (1892) | Alamy

By 1890, Smyth would return to England, throw herself into her career as a composer, and later join the women’s suffrage movement. She would also pursue relationships with other fascinating women, some of whom I’ve mentioned earlier in this post.

Ultimately, though, Smyth’s relationship with Elisabeth von Herzogenberg was one of the most meaningful in her life. Its abrupt and unresolved end haunted her, and Smyth’s coming-to-terms with the consequences of her own actions remained a lifelong struggle.

In Christopher St. John’s 1959 biography of Smyth, the author recounts a conversation between the composer and writer Vernon Lee (1856-1935). Lee asks Smyth, “‘To how many people have you given without reserve, and got something like the equivalent in return?’” Smyth responds, “‘To three; Lisl, Harry and —” (Smyth refrained from naming the third) (St. John 1959, 17). As she published Impressions That Remained in 1919, twenty-seven years after Elisabeth’s death, Smyth mentions the nickname “Lisl” over 150 times, more than any other figure in the book.

It seems then that Ethel Smyth shares a great deal with our protagonist in “Bei einer Linde” - both must rely on their memories of the past to conjure the love they once cherished. Sadly, our poem’s protagonist can never recarve their initials into the bark of the linden tree. They are left to only trace the shape of each letter through the recesses of their memories.

However, Smyth attempted to reanimate her past; she published a book to etch Elisabeth and their love onto the grains of history. While Smyth’s account may be one-sided, paired with an analysis of her Lieder (songs), we catch a glimpse into the inner lives of these two remarkable women. As Elisabeth so aptly wrote to Smyth in a letter from 1878, “And now there you are, little tree, grown into my heart with such deep roots that nothing can ever tear them out!” (Smyth, 223).

To learn more about Ethel Smyth and her incredible music, make sure you don’t miss Part I of “By a Linden Tree: The Leipzig Lieder of Composer Ethel Smyth” and check out Boulanger Initiative’s Beyond the Box: Into The Barlines, Women Composers Throughout History: Orchestra Edition! To read more of Dr. Noelle McMurtry’s writing on the song repertoire of women composers, check out her Substack, She Is Song.

Bibliography

Abromeit, Kathleen A. “Ethel Smyth, ‘The Wreckers,’ and Sir Thomas Beecham.” The Musical Quarterly 73, no. 2 (1989): 196–211. http://www.jstor.org/stable/742066.

Ashley, Tim. “The Wreckers review – Glyndebourne bring Smyth’s rarity to vivid and passionate life.” The Guardian, May 22, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2022/may/22/the-wreckers-review-glyndebourne-festival-ethel-smyth.

Blair, Elisabeth. “Women in (New) Music: Two Women and an Opera House.” Second Inversion: Rethink Classical. December 6, 2016. https://www.secondinversion.org/2016/12/08/women-in-new-music-two-women-and-an-opera-house/.

Broad, Leah. “Without Ethel Smyth and classical music's forgotten women, we only tell half the story.” The Guardian, December 2, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/dec/02/ethel-smyth-classical-music-forgotten-women-canon-composition.

Clive, Peter. “Herzogenberg, Elisabeth [Elisabet, Lisl] Von.” In Brahms and his World: A Biographical Dictionary. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006: 216-218. Google Books.

Collins Rose. “Dame Ethel Smyth.” In Portraits to the Wall: Historic Lesbian Lives Unveiled. Amazon, 2020: 166-191. Kindle.

“Dame Ethel Mary Smyth.” English National Opera. Accessed on October 5, 2024. https://www.eno.org/composers/dame-ethel-mary-smyth/.

D’Silva, Beverly. “Ethel Smyth: An extraordinary 'lost' opera composer.” BBC. July 21, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20220720-ethel-smyththe-rebel-composer-erased-from-history.

“Elisabeth von Herzogenberg: 24 Volkskinderlieder.” Carus Verlag. Accessed on June 4, 2025. https://www.carus-verlag.com/en/music-scores-and-recordings/elisabeth-von-herzogenberg-24-volkskinderlieder-1232700.html?listtype=search&searchparam=von%20herzogenberg.

Fitzmaurice, Laura. “Clotilde Brewster: American Expatriate Architect.” 19th Century Magazine, (Fall 2014): 17 -25. Internet Archive.

Fuller, Sophie. "Smyth, Dame Ethel." Grove Music Online. 2001. https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.proxy.alumni.jhu.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000026038.

Gates, Eugene. “Damned If You Do and Damned If You Don’t: Sexual Aesthetics and the Music of Dame Ethel Smyth.” The Journal of Aesthetic Education vol. 31, no.1 (1997): 63-71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3333472.

Harris, Amanda. "The Smyth-Brewster Correspondence: A Fresh Look at the Hidden Romantic World of Ethel Smyth." Women and Music: A Journal of Gender and Culture 14 (2010): 72-94. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/wam.2010.0005.

Klek, Konrad. ,,Herzogenberg - Leben und Würdigung.” Herzogenberg und Heiden. Accessed on May 23, 2025. https://www.herzogenberg.ch/hvh_wuerdigung.htm.

Lumsden, Rachel. “‘The Music Between Us’: Ethel Smyth, Emmeline Paknhurst, and ‘Possession.’” Feminist Studies vol. 41, no. 2 (2015): 335-370. https://doi.org/10.15767/feministstudies.41.2.335.

Orchard, Lewis and Di Stiff. “Dame Ethel Smyth DBE, DMus (1858-1944), composer and suffragette.” The March of the Women Project: Exploring Surrey’s Past. Accessed on October 6, 2024. https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/themes/subjects/womens-suffrage/suffrage-biographies/dame-ethel-smyth-composer-and-suffragette/.

Orchard, Lewis. “Ethel Smyth and Henry Brewster.” Exploring Surrey’s Past. April 2019. https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/9180-Ethel-Smyth-and-Henry-Brewster-edit-for-ESP.pdf.

Orchard, Lewis. “Dame Ethel Smyth - Literary Works.” Celebrate Woking. Accessed on June 14, 2025. https://www.celebratewoking.info/wokingsheritage/Dame_Ethel_Smyth/Ethel_literary_works.pdf.

Popova, Maria. “Dignity, Daring, and Disability: The Pioneering Queer Composer and Defiant Genius Ethel Smyth on Making Music While Going Deaf.” Brainpickings. Accessed October 4, 2024. https://www.brainpickings.org/2021/01/12/ethel-smyth/.

Predota, Georg. “‘Sing heavenly Muse’: Elisabeth von Herzogenberg and Johannes Brahms.” Interlude, November 25, 2017. https://interlude.hk/sing-heavenly-muse-elisabeth-von-herzogenberg-johannes-brahms/.

Reich, Nancy B. “Women as Musicians: A Question of Class.” In Musicology and Difference: Gender and Sexuality in Music Scholarship. Edited by Ruth A. Solie. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993: 125-146.

Rempe, Martin. “In a Different World: Women in Musical Life.” In Art, Play, Labour: The Music Profession in Germany (1850-1960). Leiden, The Netherlands, 2023: 103-125. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004542723_006.

Roberts, Maddy Shaw. “Composer and political activist Dame Ethel Smyth is officially a Grammy winner.” Classical fM, March 15, 2021. https://www.classicfm.com/music-news/composer-ethel-smyth-first-grammy-nomination-the-prison/.

Ruhbaum, Antje. ,,Elisabeth von Herzogenberg.” Musik und Gender im Internet (MUGi). October 2023. https://mugi.hfmt-hamburg.de/receive/mugi_person_00000363?lang=de#Biografie

Schlegel, Theresa. “Elisabeth and Heinrich von Herzogenberg.” Translated by Thomas Henninger. Schumann-Portal, 2020. https://www.schumann-portal.de/elisabeth-and-heinrich-von-herzogenberg.html.

Scott, Derek B. “The Sexual Politics of Victorian Musical Aesthetics.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 119, no. 1 (1994): 91–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrma/119.1.91.

Smyth Ethel. Impressions That Remained: Memoirs. London: Alfred A. Knopf, 1946. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/impressionsthatr010821mbp/page/n11/mode/2up.

Smyth, Ethel. The Memoirs of Ethel Smyth. Edited by Ronald Crichton. New York: Viking, 1987. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/memoirsofethelsm00smyt.

St. John, Christopher. Ethel Smyth: A Biography. London: Longmans, Gree and Co., 1959. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/bwb_O8-BQS-326/mode/2up.

Tchaikovsky Pyotr Ilyich. Autobiographical Account of a Tour Abroad in the Year 1888. English translation by Luis Sundkvist. Tchaikovsky Research, 2009. https://en.tchaikovsky-research.net/pages/Autobiographical_Account_of_a_Tour_Abroad_in_the_Year_1888#cite_note-note2-2.

Ţenche-Constantinescu Alina-Maria, Claudia Varan, Fl. Borlea., E. Madoşa, and G. Szekely.“The symbolism of the linden tree.” Journal of Horticulture, Forestry, and Biotechnology, Volume 19, no. 2 (2015): 237-242. https://journal-hfb.usab-tm.ro/romana/2015/Lucrari%20PDF/Lucrari%20PDF%2019(2)/41Tenche%20Alina%202.pdf.

Thym, Jürgen. “Song as Memory, Memory as Song.” Archiv Für Musikwissenschaft 69, no. 3 (2012): 263–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23375389.

Tick, Judith. “Women as Professional Musicians in the United States, 1870-1900.” Anuario Interamericano de Investigación Musical 9 (1973): 95-133. https://doi.org/10.2307/779908.

Wiley, Christopher. “Music and Literature: Ethel Smyth, Virginia Woolf, and ‘The First Woman to Write an Opera.’” The Musical Quarterly 96, no. 2 (2013): 263–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43866239.

Yohalem, John. “A Woman’s Opera at the Met: Ethel Smyth’s Der Wald in New York.” The Metropolitan Opera Archives. April 17, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20221114133959/http://archives.metoperafamily.org/imgs/DerWald.htm.

Zigler, Amy. “Biography.” Dame Ethel Smyth (1858-1944). Accessed on October 3, 2024. https://www.ethelsmyth.org.