“By a Linden Tree”: Discovering the Lieder of Composer Ethel Smyth

By Dr. Noelle McMurtry

Part 1

Sheepdogs, Tweeds & Bicycles

Ethel Smyth (c. 1901) | Alamy

Ethel Mary Smyth (1858-1944) was a trailblazing queer English composer, conductor, author, and suffrage activist, whose decades-long musical career spanned two centuries. She engaged with a variety of musical forms, including songs, chamber works, opera, and symphonic and choral works.

Despite the prejudice that Smyth faced as both a woman composer and a suffragist, she refused to adhere to the repressive Victorian social mores of British society. Famed Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) wryly described Smyth as “a serious and gifted composer... [not] without her peculiarities and eccentricities” (Tchaikovsky 2009).

Smyth continually defied Victorian gender stereotypes – wearing tweed suits and men’s hats, riding bicycles, golfing, mountaineering, hunting, and keeping Old English sheepdogs as her constant companions. Single by choice, Smyth had passionate affairs with both women and men.

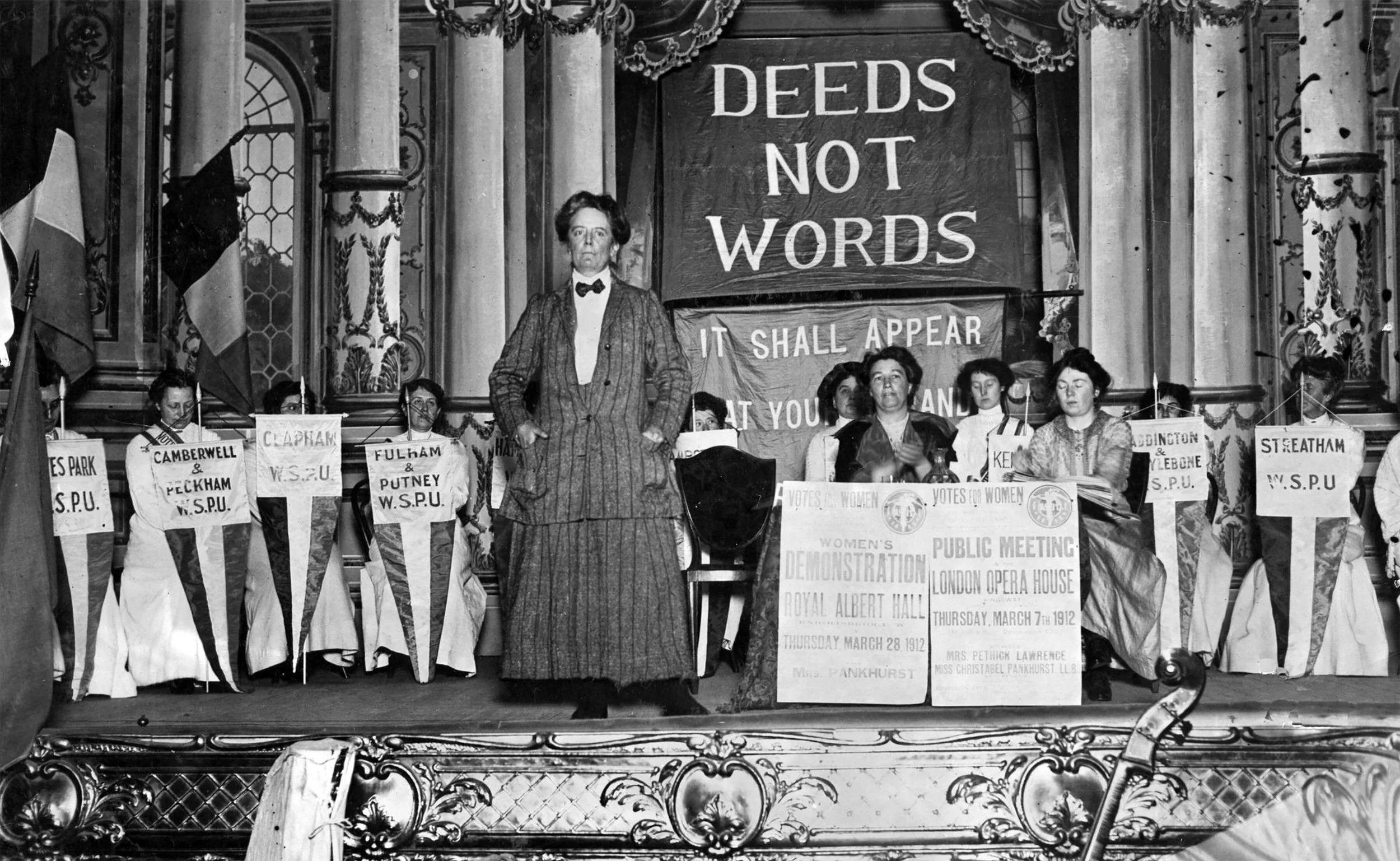

She composed six operas, published nine memoirs, fought for women’s suffrage in Great Britain with the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), and was jailed in the process. Smyth worked as a radiographer during World War I, was the first woman composer awarded Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in 1922, and was the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate in music from Oxford University in 1926.

Ethel Smyth at a meeting of the WSPU in London (1912) | Alamy

As an homage to Smyth’s intrepid spirit, it may be most fitting to begin with an introduction from the composer herself. In The Memoirs of Ethel Smyth, a 1987 anthology edited by Robert Crichton, Smyth explains to the reader why her reputation may have preceded her.

“Because I have conducted my own operas and love sheep-dogs; because I generally dress in tweeds, and sometimes, at winter afternoon concerts, have even conducted in them; because I was a militant suffragette… because I have written books, spoken speeches, broadcast, and don’t always make sure that my hat is on straight; for these and other equally pertinent reasons, in a certain sense I am well known” (Smyth 1987, 355-356).

Smyth and her first dog Marco (1891) | Impressions That Remained (1919)

After Marco, Smyth cared for Old English Sheepdogs, each named Pan, until her final years. One of Smyth's memoirs, Inordinate Affection (1936), is notably a series of sketches of her beloved dogs.

Smyth the Composer

Over four decades, Smyth composed in a wide array of musical genres - orchestral works, a mass, operas, sacred and secular choral music, song repertoire, piano works, organ works, and chamber music, including trios, string quartets, and sonatas. Smyth’s compositional style would initially be influenced by the mid-19th-century German Romantic tradition, particularly by the music of composer, conductor, and pianist Johannes Brahms (1833-1897).

Watch the second movement, "Andante," from Smyth's Sonata No. 2 in C-sharp minor (1877), featuring pianist Hanni Liang from her 2024 album "VOICES."

Her orchestral works, such as Overture to Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra (1889), Serenade in D (1889), and Mass in D (1891) exhibit hallmark traits of the late Romantic era: vivid melodies, rich chromatic harmonies, and an overwhelming sense of drama.

Listen to this 1996 recording of Smyth's Serenade in D Major with the BBC Philharmonic, conducted by Odaline de la Martinez.

The composer was also inspired by the music of her English childhood, and she incorporated elements of Anglican sacred music and English folk melodies into her compositions, such as the orchestral song cycle Three Moods of the Sea (1913) and Variations on Bonny Sweet Robin (Ophelia’s Song) (1927) for flute, oboe, and piano.

Watch Smyth's Variations on Bonny Sweet Robin (Ophelia's Song) (1927), performed by sound left behind in 2023.

Dramatic storytelling was a particular focus for Smyth, whether via programmatic elements in the orchestral tone poem On the Cliffs of Cornwall (1908), or as a composer of six operas. From the 1890s to the 1920s, Smyth contributed significantly to the 20th-century operatic repertoire, composing Fantasio (1894), Der Wald (1901), The Wreckers (1904), The Boatswain’s Mate (1914), Fête galante (1922), and Entente cordiale (1924).

In 1903, Smyth’s one-act opera Der Wald (The Forest) was the first opera by a woman composer to be performed at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. More than 100 years would pass until another opera by a woman composer appeared on the stage at the Met - the 2016 US premiere of L’Amour de Loin (Love from Afar) by Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho (1952-2023).

Listen to the 2023 premiere recording of the Prologue of Smyth's Der Wald (1901) in English translation with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and BBC Singers, conducted by John Andrews. The rest of the production is also available to listen on YouTube.

The Songs of Ethel Smyth

Smyth was often drawn to large-scale instrumental and vocal works, which comprise the majority of her compositional output. However, she did compose three collections of songs for voice and piano: Lieder & Balladen, Op. 3 (1886), Lieder, Op. 4 (1886), and Three Songs (1913) (Zigler, “Works List”).

Listen to "Possession" from Smyth's Three Songs (1913), performed by mezzo-soprano Melinda Paulsen and pianist Angela Gassenhuber on this 2012 recording of "Ethel Smyth: Kammermusik and Lieder, Vol. III."

Musicologist Rachel Lumsden notes, “… most research on Smyth has focused either on her literary endeavors or her compositions. What is missing is a thoroughgoing analysis of the connections between the two” (Lumsden 2015, 336). I find that tracking one of Smyth’s songs through her memoir, Impressions That Remained (1919), is an excellent means of better understanding both her music and her life writing.

Impressions That Remained was the first of Smyth’s nine memoirs, originally published in two volumes in 1919. It reflects on Smyth’s early childhood in Surrey in the late 1850s and concludes with her experiences in Germany and Italy as a young composer from 1877 to 1891. Smyth also includes heavily edited excerpts from her personal correspondence with various family, friends, and colleagues.

I would like to center one particular song, “Bei einer Linde” (By a Linden Tree) from Lieder & Balladen, Op. 3, amidst Smyth’s recollections in Impressions That Remained. In the 1880s, Smyth composed “Bei einer Linde” as a student in Leipzig, today the largest city in the German eastern state of Saxony.

Woodcut of Leipzig, Germany from the German magazine Die Gartenlaube (1885) | Alamy

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg | Alamy

Smyth’s time in Leipzig was formative, both musically and personally. It was there where she studied composition seriously for the first time, situating her nascent musical style within the mid- to late 19th-century German Romantic tradition. Smyth and her songs were welcomed into the salons of Leipzig’s elite “musical society,” where she would meet Austrian composer and pianist Elisabeth von Herzogenberg (1847-1892), one of the great loves of Smyth’s life.

The Loves of Ethel Smyth

Smyth engaged in queer romantic relationships with women throughout her lifetime. Within certain societal circles, Smyth’s sexuality was acknowledged, but it wasn’t publicly revealed until the composer began to author her memoirs in the early 1920s.

In these books, Smyth examines her relationships with women as friends, companions, and lovers, while also discussing complex aspects of her own sexuality. In Impressions That Remained, she acknowledged her lasting bonds with the women in her life, whose support (in various forms) had been like “shining threads.”

“Let me say here, that all my life... I have found in women’s affection a peculiar understanding, mothering quality that is a thing apart.... And further it is a fact... that the people who have helped me most at difficult moments of my musical career, beginning with my own sister Mary, have been members of my own sex. Thus, it comes to pass that my relations with certain women, all exceptional personalities I think, are shining threads in my life” (Smyth 1919, 6).

Smyth fell in love passionately and often. In “The Smyth-Brewster Correspondence: A Fresh Look at the Hidden Romantic World of Ethel Smyth,” musicologist Amanda Harris observes that “[Smyth’s] tendency to love a number of people, both women and men, was sometimes difficult for the main loves of her life to understand” (Harris 2010, 73).

Her relationships with women included the aforementioned Elisabeth von Herzogenberg, Maid of Honour to Queen Victoria and women’s rights advocate Lady Mary Ponsonby (1832-1916), suffrage activist Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928), keyboard player Violet Gordon-Woodhouse (1872-1948), and author Virginia Woolf (1882-1941).

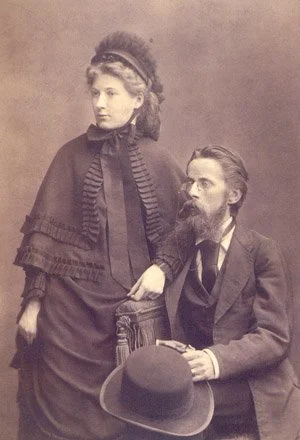

Henry Bennet Brewster (1850-1908)

Although musicologist Amanda Harris observes that “the sheer number of women Smyth fell in love with… testifies to the centrality of women in her romantic life,” she had a singularly important relationship with a man - British-American writer and philosopher Henry Bennett Brewster (1850-1908) (Harris 2010, 87).

Henry Bennet Brewster (1897) | Wikidata

Born in Paris, Brewster was the son of an American dental surgeon, who had built his career tending to wealthy European clientele. He ultimately bequeathed a sizable inheritance to Henry, who was then able to support both a family and his literary aspirations (Fitzmaurice 2014, 17).

Henry was bilingual, and he wrote philosophical treatises in English, as well as poetry in French. In 1887, he published The Theories of Anarchy and of Law, although none of his books became particularly well-known (Harris 2010, 79). Smyth and Brewster would meet for the first time in 1882, and their relationship would last for over twenty-four years until his death in 1908.

They nurtured their connection over lively debates on art, literature, philosophy, and politics. Brewster also co-wrote the librettos for Smyth’s first two operas, Fantasio and Der Wald, as well as the original French libretto for The Wreckers.

In 1930, 22 years after Henry’s death, Smyth set an orchestral cantata to his poem The Prison (1891). In this philosophical dialogue, the Prisoner and the Soul discuss how imprisonment, both physically and metaphorically, indelibly alters the human condition (Orchard 2019). Ninety years after its premiere, conductor James Blachly’s recording of The Prison won a 2021 Grammy for Best Classical Solo Vocal Album, making Smyth the first historic woman composer to ever win such an award (Roberts 2021).

The Battle for Leipzig

Smyth’s childhood was spent in Frimley, Surrey. As one of eight siblings in a military family, she discovered her life-long passion for musical composition as a child. Ethel’s conservative father, John Hall Smyth (1815-1894), was a Major-General in the Royal Artillery, and he fiercely disapproved of his daughter’s musical interests.

With the enduring support of her mother Emma Struth Smyth (1824-1891), Ethel never lost sight of her goal: to study composition at the famed Konservatorium der Musik in Leipzig, which had been founded in 1843 by composers Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) and Robert Schumann (1810-1856) and was the oldest public conservatory in Germany.

The Konservatorium der Musik in Leipzig, based on a watercolor by Anton von Lewy (1886) | Alamy

However, Smyth’s father refused to allow his daughter to travel to Leipzig. In retaliation, she waged a campaign to wear down his defenses. After years spent arguing, locking herself in her room, and refusing to attend social gatherings, nineteen-year-old Smyth prevailed.

In 1877, she arrived at the Leipzig Konservatorium to study composition. Smyth’s stubborn determination to pursue a German conservatory education, expressly against her father’s wishes, represents one of many instances in which she would refuse to bend under societal pressure.

Smyth & The Herzogenbergs

Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1900) | Wikipedia

Within a year of her matriculation at the Konservatorium, Smyth encountered another setback. After dealing with sub-par instruction from her teachers, she left the school. Ever resilient, Smyth decided to remain in Leipzig and soon found herself a private composition teacher – Austrian composer and conductor Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1843-1900). He was respected in musical circles for his knowledge of the music of J.S. Bach (1685-1750) and contrapuntal techniques.

As a soon-to-be fixture in the Herzogenberg household, Smyth entered into a seven-year romance with his wife Elisabeth, who was also a pianist and composer. Their intimacy would define “the happiest years of [Smyth’s] early life,” and the eventual rupture of their relationship would later break Smyth’s heart (Smyth 1919, 182).

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg (1847-1892)

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg (1877) | Alamy

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg (née von Stockhausen) was born in Paris into a family of German aristocrats. Her father, Bodo Albrecht von Stockhausen (1810-1885), served as a diplomat in the Hanoverian Court. Her mother, Clothilde Annette (1818-1891), was a Countess of the noble German Baudissin family. Elisabeth’s father was an avid amateur pianist, studying in Paris with Polish virtuoso pianist and composer Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849).

In 1853, the Stockhausens moved to Vienna, where Bodo Albrecht had been named ambassador to the Viennese Court. In Vienna, Elisabeth and her two older sisters benefited from a formal education. They were also exposed to the arts, attending opera and concert performances in aristocratic circles.

Elisabeth eventually studied piano with Julius Epstein (1832-1926), a renowned Croatian piano pedagogue. She also briefly took piano lessons with German composer Johannes Brahms, who would later become a life-long friend and musical confidante.

Elisabeth fascinated all who knew her, and she was admired for her intelligence, beauty, and musical talents. As Smyth recalled from their first meeting, Elisabeth was ever multifaceted – a strikingly beautiful “siren,” a “genius” with a sharp mind, and an aristocratic host who was unexpectedly a “Heaven-inspired cook” (Smyth 1919, 170).

“At the time I first met her she was twenty-nine, not really beautiful but better than beautiful, at once dazzling and bewitching; the fairest of skins, fine-spun, wavy golden hair, curious arresting greenish-brown eyes, and a very noble rather low forehead, behind which you knew there must be an exceptional brain… It really was true that with her sunshine came in at the door, and both sexes succumbed equally to her charm” (Smyth 1919, 169).

Elisabeth and Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1891) | Wikipedia

Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1843-1900)

In Vienna, Elisabeth would meet Heinrich von Herzogenberg, a descendant of French nobility and the son of an Austrian court official. In 1861, he had pursued law and philosophy studies at the University of Vienna, only to abandon his degree for a career in music a year later.

Despite their different religions (he was a Catholic; she a Protestant), Elisabeth and Heinrich were married in 1868. They lived for a time in Graz, where Heinrich worked as a freelance composer, finally settling together in Leipzig in 1874. By Smyth’s account, the Herzogenberg marriage was “notoriously happy,” a respectful partnership in which “she was as devoted to him as he to her” (Smyth 1919, 170-173).

Inspired by their abiding love of music, the Herzogenbergs cultivated a salon in Leipzig, which attracted illustrious creatives of the day, including our protagonist Ethel Smyth, Hungarian virtuoso violinist Joseph Joachim (1831-1907) and Austrian-German contralto Amalie Joachim (1839-1899), German pianist and composer Clara Schumann (1819-1896), as well as German composer Johannes Brahms.

Elisabeth the Composer

Elisabeth was a talented composer and pianist. Smyth described her as a “... musical genius. Almost by instinct she read and played from score as do few routined conductors, and in judgment, critical faculty, and all-round knowledge was the perfect musician” (Smyth 1919, 170).

Only three of Elisabeth’s compositions have ever been published – two during her lifetime (24 Volkskinderlieder and “Nachklang” in her husband’s Gesänge und Balladen, Op. 44) and one immediately after her death (Acht Klavierstücke).

Watch pianist Roberta Ubaldo perform Elisabeth von Herzogenberg's Acht Klavierstücke (1892) in the 2021 concert "L'ombra illuminata. Donne nella musica." Her performance begins at 0:40.

Influenced by the music of mid-19th-century German composers Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, and Johannes Brahms, Elisabeth never publicly promoted her own compositions. Musicologist Antje Ruhbaum notes that no primary source, such as letters, survives to verify if Elisabeth’s works were ever privately performed (Ruhbaum 2023).

Elisabeth revealed certain frustrations to Smyth about the trajectory of her musical career (Ruhbaum 2023). In July 1878, she cautioned Smyth against allowing momentary pleasures, like lawn tennis and dancing, to distract from her musical studies, writing,

“Ethel, beware lest it should be with you as with me. ... I often could weep to think of the time I have lost, how badly I have husbanded my little talent. And now here I am — for all my artist's soul in the bonds of wretched dilettantism! If you knew what pain my conscience gives me… you would do anything to avoid such a fate” (Smyth 1919, 269).

In Elisabeth’s warning to Smyth, it’s also worth noting how her conception of her own artistry was heavily influenced by gendered stereotypes. Without sufficiently “husbanding” her talent - a masculinized form of caretaking - she remained trapped in the ranks of amateurs, a belittling label that was often reserved for the domestic musical activities of women.

Socio-Economic Class & The 19th-Century Woman Musician

Young Victorian woman playing a piano, based off an engraving from the British magazine, The Girl's Own Paper (1883) | Alamy

Elisabeth’s confession about her unrealized creative potential illustrates how her relationship to music ultimately diverged from Smyth’s. Both women benefited from their societal status in pursuit of a musical education. However, as musicologist Nancy B. Reich outlines in “Women As Musicians: A Question of Class,” Elisabeth’s aristocratic background also hindered her musical development.

By the turn of the 19th Century in Europe, Reich argues that two groups of women musicians had emerged – the “professional woman musician” and the “nonprofessional woman musician” (Reich 1993, 126). For Reich, the 19th-century professional woman musician was a working artist. She existed on a lower economic rung and relied on her creative efforts to support herself and her family. She performed publicly, published her music, and toured.

Conversely, the 19th-century non-professional woman musician came from an aristocratic or monied background with access to a musical education. She rarely made money from her musical activities, which were confined to private performances for family and friends. She did engage, though, in more public musical acts, such as organizing salons, which were an important means of artistic networking, music-making, and creative connection throughout the 19th Century (Reich 1993, 126-127).

While “non-professional” women musicians, like Elisabeth von Herzogenberg, developed sophisticated skills in performance and composition, sometimes akin to the level of any professional, their efforts often remained hidden behind closed doors, which could stymie their musical output (Reich 1993, 127-129).

Despite Smyth’s upper middle-class English background, her fate was entirely different. She successfully crossed from the ranks of the “non-professional” into the professional realm. This transformation was supported by several factors - Smyth was never pressured to marry, she chose to remain single, and she received a modest monthly allowance from her family to pursue composition.

Although their career trajectories ultimately diverged, music remained a shared passion for Smyth and Elisabeth, an illuminating space where both women saw each other most clearly. Smyth recalled,

“In musical matters Lisl [Elisabeth] and I saw absolutely eye to eye, and it was a strange intoxicating thing to realize that in moments of musical ecstasy the heart of the being on earth you loved best was so absolutely at one with yours that it might have been the same heart” (Smyth 1919, 232).

To learn more about Ethel Smyth and her incredible music, stay tuned for Part II of “By a Linden Tree: The Leipzig Lieder of Composer Ethel Smyth” and check out Boulanger Initiative’s Beyond the Box: Into The Barlines, Women Composers Throughout History: Orchestra Edition! To read more of Dr. Noelle McMurtry’s writing on the song repertoire of women composers, check out her Substack, She Is Song.

Bibliography

Abromeit, Kathleen A. “Ethel Smyth, ‘The Wreckers,’ and Sir Thomas Beecham.” The Musical Quarterly 73, no. 2 (1989): 196–211. http://www.jstor.org/stable/742066.

Ashley, Tim. “The Wreckers review – Glyndebourne bring Smyth’s rarity to vivid and passionate life.” The Guardian, May 22, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2022/may/22/the-wreckers-review-glyndebourne-festival-ethel-smyth.

Blair, Elisabeth. “Women in (New) Music: Two Women and an Opera House.” Second Inversion: Rethink Classical. December 6, 2016. https://www.secondinversion.org/2016/12/08/women-in-new-music-two-women-and-an-opera-house/.

Broad, Leah. “Without Ethel Smyth and classical music's forgotten women, we only tell half the story.” The Guardian, December 2, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/dec/02/ethel-smyth-classical-music-forgotten-women-canon-composition.

Clive, Peter. “Herzogenberg, Elisabeth [Elisabet, Lisl] Von.” In Brahms and his World: A Biographical Dictionary. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006: 216-218. Google Books.

Collins Rose. “Dame Ethel Smyth.” In Portraits to the Wall: Historic Lesbian Lives Unveiled. Amazon, 2020: 166-191. Kindle.

“Dame Ethel Mary Smyth.” English National Opera. Accessed on October 5, 2024. https://www.eno.org/composers/dame-ethel-mary-smyth/.

D’Silva, Beverly. “Ethel Smyth: An extraordinary 'lost' opera composer.” BBC. July 21, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20220720-ethel-smyththe-rebel-composer-erased-from-history.

“Elisabeth von Herzogenberg: 24 Volkskinderlieder.” Carus Verlag. Accessed on June 4, 2025. https://www.carus-verlag.com/en/music-scores-and-recordings/elisabeth-von-herzogenberg-24-volkskinderlieder-1232700.html?listtype=search&searchparam=von%20herzogenberg.

Fitzmaurice, Laura. “Clotilde Brewster: American Expatriate Architect.” 19th Century Magazine, (Fall 2014): 17 -25. Internet Archive.

Fuller, Sophie. "Smyth, Dame Ethel." Grove Music Online. 2001. https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.proxy.alumni.jhu.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000026038.

Gates, Eugene. “Damned If You Do and Damned If You Don’t: Sexual Aesthetics and the Music of Dame Ethel Smyth.” The Journal of Aesthetic Education vol. 31, no.1 (1997): 63-71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3333472.

Harris, Amanda. "The Smyth-Brewster Correspondence: A Fresh Look at the Hidden Romantic World of Ethel Smyth." Women and Music: A Journal of Gender and Culture 14 (2010): 72-94. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/wam.2010.0005.

Klek, Konrad. ,,Herzogenberg - Leben und Würdigung.” Herzogenberg und Heiden. Accessed on May 23, 2025. https://www.herzogenberg.ch/hvh_wuerdigung.htm.

Lumsden, Rachel. “‘The Music Between Us’: Ethel Smyth, Emmeline Paknhurst, and ‘Possession.’” Feminist Studies vol. 41, no. 2 (2015): 335-370. https://doi.org/10.15767/feministstudies.41.2.335.

Orchard, Lewis and Di Stiff. “Dame Ethel Smyth DBE, DMus (1858-1944), composer and suffragette.” The March of the Women Project: Exploring Surrey’s Past. Accessed on October 6, 2024. https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/themes/subjects/womens-suffrage/suffrage-biographies/dame-ethel-smyth-composer-and-suffragette/.

Orchard, Lewis. “Ethel Smyth and Henry Brewster.” Exploring Surrey’s Past. April 2019. https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/9180-Ethel-Smyth-and-Henry-Brewster-edit-for-ESP.pdf.

Orchard, Lewis. “Dame Ethel Smyth - Literary Works.” Celebrate Woking. Accessed on June 14, 2025. https://www.celebratewoking.info/wokingsheritage/Dame_Ethel_Smyth/Ethel_literary_works.pdf.

Popova, Maria. “Dignity, Daring, and Disability: The Pioneering Queer Composer and Defiant Genius Ethel Smyth on Making Music While Going Deaf.” Brainpickings. Accessed October 4, 2024. https://www.brainpickings.org/2021/01/12/ethel-smyth/.

Predota, Georg. “‘Sing heavenly Muse’: Elisabeth von Herzogenberg and Johannes Brahms.” Interlude, November 25, 2017. https://interlude.hk/sing-heavenly-muse-elisabeth-von-herzogenberg-johannes-brahms/.

Reich, Nancy B. “Women as Musicians: A Question of Class.” In Musicology and Difference: Gender and Sexuality in Music Scholarship. Edited by Ruth A. Solie. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993: 125-146.

Rempe, Martin. “In a Different World: Women in Musical Life.” In Art, Play, Labour: The Music Profession in Germany (1850-1960). Leiden, The Netherlands, 2023: 103-125. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004542723_006.

Roberts, Maddy Shaw. “Composer and political activist Dame Ethel Smyth is officially a Grammy winner.” Classical fM, March 15, 2021. https://www.classicfm.com/music-news/composer-ethel-smyth-first-grammy-nomination-the-prison/.

Ruhbaum, Antje. ,,Elisabeth von Herzogenberg.” Musik und Gender im Internet (MUGi). October 2023. https://mugi.hfmt-hamburg.de/receive/mugi_person_00000363?lang=de#Biografie

Schlegel, Theresa. “Elisabeth and Heinrich von Herzogenberg.” Translated by Thomas Henninger. Schumann-Portal, 2020. https://www.schumann-portal.de/elisabeth-and-heinrich-von-herzogenberg.html.

Scott, Derek B. “The Sexual Politics of Victorian Musical Aesthetics.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 119, no. 1 (1994): 91–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrma/119.1.91.

Smyth Ethel. Impressions That Remained: Memoirs. London: Alfred A. Knopf, 1946. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/impressionsthatr010821mbp/page/n11/mode/2up.

Smyth, Ethel. The Memoirs of Ethel Smyth. Edited by Ronald Crichton. New York: Viking, 1987. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/memoirsofethelsm00smyt.

St. John, Christopher. Ethel Smyth: A Biography. London: Longmans, Gree and Co., 1959. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/bwb_O8-BQS-326/mode/2up.

Tchaikovsky Pyotr Ilyich. Autobiographical Account of a Tour Abroad in the Year 1888. English translation by Luis Sundkvist. Tchaikovsky Research, 2009. https://en.tchaikovsky-research.net/pages/Autobiographical_Account_of_a_Tour_Abroad_in_the_Year_1888#cite_note-note2-2.

Ţenche-Constantinescu Alina-Maria, Claudia Varan, Fl. Borlea., E. Madoşa, and G. Szekely.“The symbolism of the linden tree.” Journal of Horticulture, Forestry, and Biotechnology, Volume 19, no. 2 (2015): 237-242. https://journal-hfb.usab-tm.ro/romana/2015/Lucrari%20PDF/Lucrari%20PDF%2019(2)/41Tenche%20Alina%202.pdf.

Thym, Jürgen. “Song as Memory, Memory as Song.” Archiv Für Musikwissenschaft 69, no. 3 (2012): 263–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23375389.

Tick, Judith. “Women as Professional Musicians in the United States, 1870-1900.” Anuario Interamericano de Investigación Musical 9 (1973): 95-133. https://doi.org/10.2307/779908.

Wiley, Christopher. “Music and Literature: Ethel Smyth, Virginia Woolf, and ‘The First Woman to Write an Opera.’” The Musical Quarterly 96, no. 2 (2013): 263–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43866239.

Yohalem, John. “A Woman’s Opera at the Met: Ethel Smyth’s Der Wald in New York.” The Metropolitan Opera Archives. April 17, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20221114133959/http://archives.metoperafamily.org/imgs/DerWald.htm.

Zigler, Amy. “Biography.” Dame Ethel Smyth (1858-1944). Accessed on October 3, 2024. https://www.ethelsmyth.org.